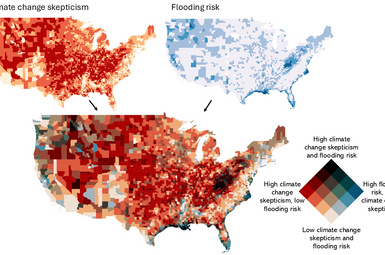

In certain parts of the U.S., the ability of residents to prepare for and respond to flooding is being undercut on three different levels.

As climate change becomes more pronounced, so too does the size, impact, and prevalence of extreme weather events. University of Michigan specialists are examining ever-increasing natural disasters, the upheaval they wreak on impact communities, and how local authorities can better manage them. U-M researchers have focused on extreme weather that ranges from regional events, like Great Lakes flooding and polar vortices, to droughts, hurricanes, wildfires, and tsunamis that carry a global toll.

In certain parts of the U.S., the ability of residents to prepare for and respond to flooding is being undercut on three different levels.

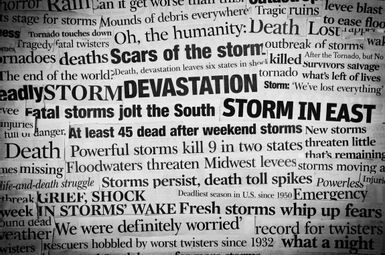

Massive 2014 flooding event in southeast Michigan showed why systems thinking beats local thinking in flood protection.

Anyone who’s spent their winter months around the Great Lakes has probably had the uncanny experience of living through three seasons in a single weekend. According to new research from U-M, these wild weather swings are poised to become even more common in the future.

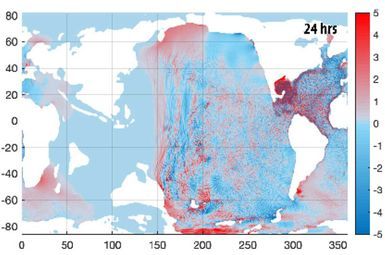

As sea ice disappears and grows less reflective, the Arctic has lost around a quarter of its cooling power since 1980, and the world has lost up to 15%, according to new research led by U-M scientists.

A recent University of Michigan study exposes a gap in sociology: a lack of focus on climate change. Societies fuel and face the consequences of this crisis, but sociology as a discipline appears insufficiently engaged with the issue, says Sofia Hiltner, U-M doctoral candidate in sociology.

“Clarity on vulnerable subgroups more susceptible to heat-related deaths will enable policymakers to design effective intervention strategies targeted to these subgroups. Downstream, this will ensure greater climate action equity.”

Nearly half of the young people surveyed on disaster preparedness indicated they felt unprepared for any type of disaster event during a period when catastrophic climate disasters are becoming increasingly frequent, says a U-M researcher.

Extreme heat is America’s deadliest weather hazard, killing more people than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined. Yet one obvious solution – increasing access to indoor cooling – is hindered by a lack of reliable data on which households have working air conditioning.

The ice-out, declared on March 16 this year, comes after the latest-recorded Douglas Lake “ice-in” occurred on Jan. 6—making this the shortest season of lake ice cover recorded at the U-M Biological Station, at 70 days. For 93 years, scientists at the Biological Station, the 10,000-acre research and teaching campus nestled along Douglas Lake near Pellston in the northern Lower Peninsula, have made the calls based on their observations of the lake.

The global challenges posed by climate change are widespread, impacting various aspects of human life, with water resources at the forefront of these challenges. As climate change advances, it is projected to exacerbate water scarcity and access issues, given the intensification of water-related hazards (such as hurricanes and flooding) and rising temperatures that will lead to sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion.

Fiber optic cables that line ocean floors could provide a less expensive, more comprehensive alternative to the current buoys that act as early warning systems for tsunamis, says a U-M researcher.

This winter, researchers at the U-M Biological Station in northern Michigan are strengthening their snow science with new technology to track the snowpack at an hourly rate and get a deeper understanding of the complexities of global environmental change.

Four newly awarded sustainability “catalyst grants” at U-M are piloting innovative ways to bolster climate resilience and sustainability. Funded by the U-M Graham Sustainability Institute, these projects will explore renewable energy deployment in Nepal, climate justice in the Midwest, textile recycling innovation and equitable transportation planning.

Climate change is reshaping forests differently across the United States, according to a new analysis of U.S. Forest Service data. With rising temperatures, escalating droughts, wildfires and disease outbreaks taking a toll on trees, researchers warn that forests across the American West are bearing the brunt of the consequences.

"“And the warming will continue to accelerate until we halt the burning of fossil fuels. This means continued worsening extreme heat and heat waves, but also many other worsening climate extremes driven by warmer temperatures. More severe droughts, more intense rainfall, more devastating hurricanes and bigger, more widespread wildfires."

Concern for climate change grows—along with support for policies to reduce emissions—when people read about Americans being forced to move within the U.S. because of it. That’s in sharp contrast to learning about climate-induced moves to the U.S. by non-Americans, which doesn’t move the dial on climate change beliefs or policy support.

Rackham student and sociologist Joyce Ho’s research seeks to understand homeowners’ experiences and insurance companies’ responses in the aftermath of forest fires in northern California.

Ann Arbor and other cities across the Midwest and Northeast have been referred to by climate specialists as “climate havens,” natural areas of refuge that are relatively safe from extreme weather events such as intense heat and tropical storms.

"In many parts of the world, the air pollution monitoring network is inadequate, so people just don't know how bad pollution is in their neighborhoods. And even when they have a monitor nearby, households might not be aware of the full range of health damages that they could be experiencing. So people don't always take adequate measures to protect themselves."

Savannas and grasslands in drier climates around the world store more heat-trapping carbon than scientists thought they did and are helping to slow the rate of climate warming, according to a new study.

U-M researchers will lead a new effort to strengthen the climate change resilience of vulnerable communities that span international boundaries and jurisdictions. The U.S. National Science Foundation has awarded $5 million to U-M to establish the Global Center for Understanding Climate Change Impacts on Transboundary Waters.

“Water conservation and access” brings a slew of images to mind: wastewater flowing through main lines to a city treatment plant, a fisherman yanking invasive mussels off the hull of a trawler, the installation of filters in communities that lack access to safely managed drinking water.

A new University of Michigan-led study finds that farmers in India have adapted to warming temperatures by intensifying the withdrawal of groundwater used for irrigation. If the trend continues, the rate of groundwater loss could triple by 2080, further threatening India’s food and water security.

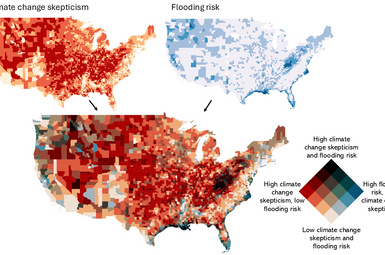

The devastating floods that ripped through the northeast United States are among the most recent in a long string of severe flooding events occurring worldwide, which make it plain that better flood predictions and safety plans are needed. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, flooding causes $8 billion in losses on average annually in the U.S. alone.

No amount of air pollution is good for the brain, but wildfires and the emissions resulting from agriculture and farming in particular may pose especially toxic threats to cognitive health, according to new research from U-M. Increasingly, evidence shows exposure to air pollution makes the brain susceptible to dementia.

The risk of death rises among older adults with Alzheimer’s or other dementias in the months following exposure to a hurricane, a new U-M study shows. Their increased risk could be due to disruption of normal routine, such as access to caregiving, changes in living environment, loss in access to medications, and change in daily routines, said study first author Sue Anne Bell, assistant professor at the U-M School of Nursing.

“I wish to use this fellowship to answer these questions in the context of Mexico, documenting through “day in the life”-style illustrations of various people and communities interacting with water. I hope my findings can be transferable to other countries and regions facing similar challenges.”

The Graham Sustainability Institute’s Carbon Neutrality Acceleration Program (CNAP) announced $1,160,000 in funding for six new faculty research projects. They tackle a range of carbon neutrality topics and augment the CNAP portfolio, which addresses six critical technological and social decarbonization opportunities: energy storage; capturing, converting, and storing carbon; changing public opinion and behavior; ensuring an equitable and inclusive transition; material and process innovation; and transportation and alternative fuels.

A new analysis of more than 20,000 trees on five continents shows that old-growth trees are more drought tolerant than younger trees in the forest canopy and may be better able to withstand future climate extremes.

Global climate talks in Egypt are heading into the home stretch with many issues still unresolved. Negotiators from nearly 200 countries have gathered in Sharm el-Sheikh for the COP27 conference in an effort to curb greenhouse gas emissions and avoid the worst ravages of climate change.

When an emergency causes a disruption in access to clean water, it seems reasonable to respond by providing the public with bottled water. In the short term, this can provide a safe supply of water while the problems get sorted out. But what if the emergency has lasted eight years, and counting, as it has in Flint, Michigan?

Flooding is the leading cause of property damage and deaths in the U.S. It’s bigger than earthquakes and forest fires put together. Branko Kerkez, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, and his students at the Digital Water Lab partnered with researchers at the U-M Center for Social Solutions to measure, better understand and prevent flooding and its aftermath in some of the most vulnerable communities.

Communities in the Great Lakes region need to start planning now for a future that may include “climate migrants” who leave behind increasingly frequent natural disasters in other parts of the country. And user-friendly web-based tools can be a central part of that planning process.

The miles-wide asteroid that struck Earth 66 million years ago wiped out nearly all the dinosaurs and roughly three-quarters of the planet’s plant and animal species. It also triggered a monstrous tsunami with mile-high waves that scoured the ocean floor thousands of miles from the impact site on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, according to a new U-M led study.

Many small and mid-sized communities like Goshen, IN simply don’t have the resources to tackle a global crisis like climate change on their own. So in 2018, Goshen was one of 12 cities that partnered with Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments (GLISA), an organization led by U-M that’s working to help small and mid-sized cities plan for a future that will be shaped by a changing climate.

"We can’t stop natural climate variability and the extreme weather La Niña can bring, so we must instead accelerate our efforts to stop the human-driven climate change that is relentlessly turning so many climate extremes into unprecedented disaster and suffering."

"Water levels are getting lower and lower because of two big problems. First, the long agreed-upon annual allocation of water to about 40 million users in seven states (e.g., California) and Mexico exceeds the supply of water flowing in the river. Second, and ignored by many, the water flowing in the river is also dropping relentlessly, as a warmer, drier climate reduces the amount from snow and rain that reaches the river."

As a board member of the nonprofit Cass Community Social Services organization in Detroit, SEAS master’s student Isabella Shehab has seen firsthand the challenges the city and its residents face: vacant buildings, aging infrastructure, flooding. Now, Shehab is using a scholarship awarded through the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) to research the impacts these challenges have on Detroit residents’ mental health and well-being—all with an eye on solutions.

Floods are complex events, and they are about more than just heavy rain. Each community has its own unique geography and climate that can exacerbate flooding, so preparing to deal with future floods has to be tailored to the community.

From the Great Lakes to its inland rivers and streams, hiking trails to golf courses, and lakeside cottages to campgrounds, the State of Michigan has long offered a near-endless number of natural resources to enjoy each summer—and a thriving tourism industry to prove it. But like with the rest of the country, and planet, the effects of climate change not only loom in the distance, but are here and causing real challenges to our ecosystem, and the outdoor recreation it provides, right now.

"Our growing global warming and heat wave problem is scorching our economy in many ways, racking up a trillion-dollar-plus price tag in the U.S. alone. Impacts are often highest locally where extreme heat occurs, but global supply chains are also at increasing risk due to heat-supercharged extremes, including drought, wildfire, flooding and deadly storms."

School for Environment and Sustainability dean Jonathan Overpeck: "Although a great deal is known about the problem, its cause, and its solutions, the crisis just keeps growing due to the lack of rapid action to combat it."

Maps of the American West have featured ever darker shades of red over the past two decades. The colors illustrate the unprecedented drought blighting the region. In some areas, conditions have blown past severe and extreme drought into exceptional drought. But rather than add more superlatives to our descriptions, one group of scientists believes it’s time to reconsider the very definition of drought.

How do human and social capital affect people in the aftermath of a disastrous shock? Ford School professor Elisabeth Gerber and School for Environment and Sustainability professor Arun Agrawal examined the question with data gathered before and after the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal, using a novel machine-learning based analytical approach.

Without a sustainable water supply, life in the desert is all but impossible. Flows of the Colorado are steadily shrinking because it’s snowing and raining less in the headwaters. Even bigger reductions in river flow have occurred due to the impact of relentless global warming.