Humanity can farm more food from the seas to help feed the planet while shrinking mariculture’s negative impacts on biodiversity, according to new research led by the University of Michigan.

As the built environment continues to encroach on the natural, delicate ecosystems come under ever-urgent threats. Researchers at the University of Michigan are taking a focused, multifaceted lens to a global problem — assessing human-exacerbated “dead zones” in the Gulf of Mexico and Lake Erie, noting the resilience of invasive species enabled by human activity, and analyzing the impacts of our changing climate on the health and behavior of different species and ecosystems. Experts at the School for the Environment and Sustainability (SEAS), the LSA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and the Graham Sustainability Institute are shedding a light on how humans have disrupted ecosystems, and how they can better protect and restore them in the future.

Humanity can farm more food from the seas to help feed the planet while shrinking mariculture’s negative impacts on biodiversity, according to new research led by the University of Michigan.

A new study authored by University of Michigan highlights the opportunity for animal tracking data to help usher in a new era of conservation.

In a new long-term ecological experiment, researchers showed that elevated levels of carbon dioxide nearly tripled species losses in grasslands attributed to the long-term application of simulated nitrogen pollution.

The impacts of climate change can take varying degrees of time to show up in ecosystems but, in grasslands, the response to climate change is apparent almost in real-time, according to new research by the University of Michigan. In other words, forests accumulate climate debt while grasslands are paying as they go, said the study’s lead authors, University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) Associate Professor Kai Zhu and Yiluan Song, a postdoctoral fellow in the Michigan Institute for Data and AI in Society affiliated with the Institute for Global Change Biology in SEAS.

Hundreds of terrestrial and aquatic animal species live in the Boca do Mamirauá Reserve, located in the upper reaches of the Amazon, at the confluence of the Solimões and Japurá rivers. It is the first destination of the U-M Pantanal Partnership students this year.

The Maasai Mara National Reserve was established to protect wildlife, yet it has seen populations shrink among its large, iconic herbivores, including zebras, impalas and elephants, over the last few decades.

U-M has received a $25 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to support collaborative research initiatives addressing critical environmental challenges in U.S. coastal communities.

Artisanal and small-scale mining plays a critical role in supplying the world with minerals vital for decarbonization, but this kind of mining typically lacks regulation and can be socially and environmentally harmful.

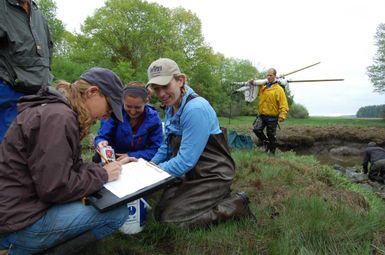

Wetlands are threatened by a variety of factors, including nutrient runoff from lawns and agricultural operations. This excess of nutrients can promote the growth of invasive species and disrupt the delicate ecosystem balance.

The soils of northern forests are key reservoirs that help keep the carbon dioxide that trees inhale and use for photosynthesis from making it back into the atmosphere. But a unique experiment is showing that, on a warming planet, more carbon is escaping the soil than is being added by plants.

Greater human-wildlife overlap could lead to more conflict between people and animals, say the U-M researchers. But understanding where the overlap is likely to occur—and which animals are likely to interact with humans in specific areas—will be crucial information for urban planners, conservationists and countries that have pledged international conservation commitments.

A team of scientists, including a U-M aquatic ecologist, is forecasting an above-average summer “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico covering about 5,827 square miles—an area roughly the size of Connecticut.

Michigan is home to 43 species of native freshwater mussels, 30 of which are considered to be at risk of extinction. Among the many factors that threaten the hard-shelled bottom dwellers are competition from invasive zebra and quagga mussels, water pollution, and—especially—dams.

The U-M Biological Station, a more than 10,000-acre research and teaching campus along Douglas Lake just south of the Mackinac Bridge, will host distinguished scientists, artists and authors from across the United States as part of its 2024 Summer Lecture Series.

As the world faces the loss of a staggering number of species of animals and plants to endangerment and extinction, one U-M scientist has an urgent message: Chemists and pharmacists should be key players in species conservation efforts.

One of the most important things people can do to address climate change is talk about it, climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe said. Citing statistics that two-thirds of people in the United States are worried about climate change, but only 8% are activated to do something about it, Hayhoe said talking about climate change doesn’t mean trying to change the minds of those who believe it is a hoax.

In the fall of 1881, with the opening of the School of Political Science, Professor Volney M. Spalding began teaching what was considered the first forestry course in the United States.

When climate scientists look to the future to determine what the effects of climate change may be, they use computer models to simulate potential outcomes such as how precipitation will change in a warming world. But U-M scientists are looking at something a little more tangible: coral.

Six new research projects will investigate the shifting dynamics of harmful algal blooms, economic trends in coastal communities, emerging fish viruses, and other issues relevant to the Great Lakes.

New, nontoxic materials could one day keep solar panels and airplane wings ice-free, or protect first responders from frostbite and more, thanks to a new U-M-led project funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Existing materials used to accomplish these feats come with serious downsides. For instance, road salts prevent pavements and streets from freezing but also corrode concrete and enter natural freshwaters through runoff, to the detriment of aquatic life.

This winter, researchers at the U-M Biological Station in northern Michigan are strengthening their snow science with new technology to track the snowpack at an hourly rate and get a deeper understanding of the complexities of global environmental change.

Climate change is reshaping forests differently across the United States, according to a new analysis of U.S. Forest Service data. With rising temperatures, escalating droughts, wildfires and disease outbreaks taking a toll on trees, researchers warn that forests across the American West are bearing the brunt of the consequences.

A conservation easement permanently protects private land by limiting the type and amount of development on a property, and restricting other uses that would damage natural features such as rich soils and high functioning wetlands.

Since 1930, U-M has maintained the Edwin S. George Reserve (ESGR) to provide research and educational opportunities, as well as preserve native flora and fauna. The 525-hectare fenced ESGR is located in Livingston County, Michigan (about 25 miles northwest of Ann Arbor) and hosts students, postdocs and faculty as well as biologists from other universities throughout the year.

This summer’s Chesapeake Bay “dead zone” was the smallest it’s been since monitoring began in 1985, according to data released by the Chesapeake Bay Program’s monitoring partners: the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Old Dominion University and Virginia Institute of Marine Science. The model used to make the annual forecasts was developed at U-M.

New research suggests that a realistic estimate of additional global forest carbon-storage potential is approximately 226 gigatonnes of carbon—enough to make a meaningful contribution to slowing climate change.

“Elephants, in a way, are the giant versions of canaries in a mine for the planet. If we cannot sustain animals as big and as capable and as versatile as elephants, then that means we have ripped a hole in the fabric of life on Earth in a way that could actually be very dangerous to ourselves. It could lead to our own demise.”

Humans and wildlife, including large carnivores, interact at an unprecedented scale as they increasingly share the world’s landscapes. A new U-M-led study of human-lion interactions found that lions tend to avoid human-dominated areas unless they are facing food scarcity and habitat fragmentation.

A new University of Michigan-led study finds that farmers in India have adapted to warming temperatures by intensifying the withdrawal of groundwater used for irrigation. If the trend continues, the rate of groundwater loss could triple by 2080, further threatening India’s food and water security.

Bird populations in the U.S. and Canada have declined by nearly 30% since the 1970s. This alarming number highlights an urgent need for action. While the issue may seem daunting on a large scale, there are significant measures we can take at the local level to help stem this loss and create a positive impact for native birds.

Producing palm oil has caused deforestation and biodiversity loss across Southeast Asia and elsewhere, including Central America. Efforts to curtail the damage have largely focused on voluntary environmental certification programs that label qualifying palm-oil sources as “sustainable.”

The hemlocks of eastern North America are threatened by the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), an invasive, sap-sucking bug that was introduced to the eastern United States from Japan in 1951. Because HWA is a nonnative species, there are no natural predators to control its population size in eastern North America, and the region’s hemlocks haven’t evolved any resistance against it, so eastern hemlocks can be sucked dry by severe HWA infestations.

Lake Erie harmful algal blooms consisting of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, are capable of producing microcystin, a known liver toxin that poses a risk to human and wildlife health. Such blooms may force cities and local governments to treat drinking water and to close beaches, and they can harm vital local economies by preventing people from fishing, swimming, boating and visiting the shoreline.

In 2023, the dead zone is predicted to be 33% smaller than the long-term average taken between 1985 and 2022. If the forecast proves accurate, this summer’s Chesapeake Bay dead zone would be the smallest on record.

Discussions of valuable but threatened ocean ecosystems often focus on coral reefs or coastal mangrove forests. Seagrass meadows get a lot less attention, even though they provide wide-ranging services to society and store lots of climate-warming carbon.

A team of scientists including a U-M aquatic ecologist is forecasting a summer “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico that will cover an estimated 4,155 square miles, which is below the 5,364-square-mile average over the 36-year history of dead zone measurements in the region.

The transmission potential of Zika or dengue in Brazil may increase by 10% to 20% in the next 30 years due to warming temperatures linked to climate change, according to U-M researchers.

This year’s theme was “Global Change and Its Consequences for Green Life,” and focused on the Direct and indirect impacts of environmental change on green life survival, reproduction, and distribution, how green life can buffer the impact of global change, evolutionary responses of green life to environmental change/stress, green life functional traits and their environmental correlates, and agroecology.

In 1973, toxic flame retardant was mistakenly sent to Michigan farmers as livestock feed, causing an environmental health crisis. To this day, researchers continue to investigate the health effects of the contamination, and community members are active in advocating for clean-up efforts.

Birds across the Americas are getting smaller and longer-winged as the world warms, and the smallest-bodied species are changing the fastest.

"A lot of people think plants are boring because they don’t move in the way animals do, but I think it makes them especially interesting. Plants can’t run away from a creature trying to eat them but, instead, they have more interesting defense mechanisms to protect themselves."

There’s been a well-documented shift toward earlier springtime flowering in many plants as the world warms. The trend alarms biologists because it has the potential to disrupt carefully choreographed interactions between plants and the creatures that pollinate them. But much less attention has been paid to changes in other floral traits, such as flower size, that can also affect plant-pollinator interactions, at a time when many insect pollinators are in global decline.

New information about an emerging technique that could track microplastics from space has been uncovered by U-M researchers. It turns out that satellites are best at spotting soapy or oily residue, and microplastics appear to tag along with that residue.

U-M researchers and their colleagues used a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown in Nepal as a natural experiment to test the responses of two GPS-collared tigers to dramatic reductions in traffic volume along a national highway. They found that traffic reductions relaxed tiger avoidance of roads: The globally endangered carnivores were two to three times more likely to cross the highway during the lockdown than before it.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the problem of emerging pathogens and the unpredictable dangers they pose for human health, but what most people don’t realize, is that the same processes that promote the emergence of human diseases—international travel and commerce, wildlife poaching, deforestation and climate change—have caused similar outbreaks of devastating pathogens in wildlife populations.