Researchers from the University of Michigan measured hormone levels in capuchin monkeys to decode how the stress response helps these monkeys weather environmental challenges.

In order to fully comprehend humanity’s impact on global ecosystems, and best inform conservation and restoration efforts going forward, it is crucial to understanding how different species adapt to our changing world. University of Michigan researchers at the School for the Environment and Sustainability (SEAS), the LSA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and the Graham Sustainability Institute are examining how organisms adjust to new habitats in an era of human-accelerated climate change, what biological underpinnings exist, and what stakeholders should bear in mind accordingly.

Researchers from the University of Michigan measured hormone levels in capuchin monkeys to decode how the stress response helps these monkeys weather environmental challenges.

Morning glory plants that can resist the effects of glyphosate also resist damage from herbivorous insects, according to a University of Michigan study.

While ticks and the maladies associated with these minute vampirish insects get a lot of media attention, lurking in the not-too-distant shadows we find several other and potentially more ominous vectors of disease—the fungal pathogens.

As the world faces the loss of a staggering number of species of animals and plants to endangerment and extinction, one U-M scientist has an urgent message: Chemists and pharmacists should be key players in species conservation efforts.

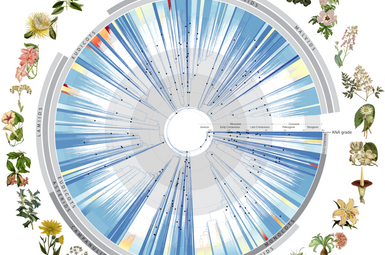

The most up-to-date understanding of the flowering plant tree of life is presented in a new study published today in the journal Nature by an international team of 279 scientists, including three U-M biologists.

Since 1930, U-M has maintained the Edwin S. George Reserve (ESGR) to provide research and educational opportunities, as well as preserve native flora and fauna. The 525-hectare fenced ESGR is located in Livingston County, Michigan (about 25 miles northwest of Ann Arbor) and hosts students, postdocs and faculty as well as biologists from other universities throughout the year.

“Elephants, in a way, are the giant versions of canaries in a mine for the planet. If we cannot sustain animals as big and as capable and as versatile as elephants, then that means we have ripped a hole in the fabric of life on Earth in a way that could actually be very dangerous to ourselves. It could lead to our own demise.”

The U-M Museum of Zoology recently acquired tens of thousands of scientifically priceless reptile and amphibian specimens, including roughly 30,000 snakes preserved in alcohol-filled glass jars. The new acquisitions boost the university’s collection of reptiles and amphibians to roughly half a million specimens, including some 70,000 snakes. With the latest additions, U-M now maintains the largest research collection of snakes anywhere in the world, according to museum curators.

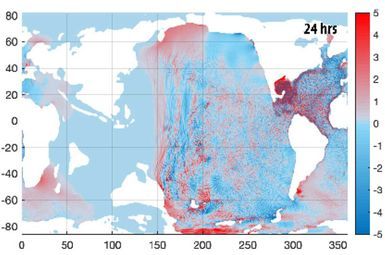

It’s well-known that birds and other animals rely on Earth’s magnetic field for long-distance navigation during seasonal migrations. But how do periodic disruptions of the planet’s magnetic field, caused by solar flares and other energetic outbursts, affect the reliability of those biological navigation systems?

Agriculture can both help and hinder: It can act as an incubator of novel animal-borne microbes, facilitating their evolution into human-ready pathogens, or it can form barriers that help block their spread.

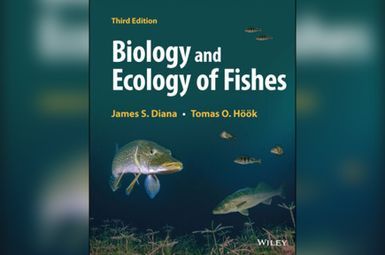

An updated textbook has been released that provides a fundamental introduction to aquatic life and ecosystems and multidisciplinary fish studies, including an understanding of the anatomical, environmental, and ethological topics of fish ecology.

The hemlocks of eastern North America are threatened by the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), an invasive, sap-sucking bug that was introduced to the eastern United States from Japan in 1951. Because HWA is a nonnative species, there are no natural predators to control its population size in eastern North America, and the region’s hemlocks haven’t evolved any resistance against it, so eastern hemlocks can be sucked dry by severe HWA infestations.

Discussions of valuable but threatened ocean ecosystems often focus on coral reefs or coastal mangrove forests. Seagrass meadows get a lot less attention, even though they provide wide-ranging services to society and store lots of climate-warming carbon.

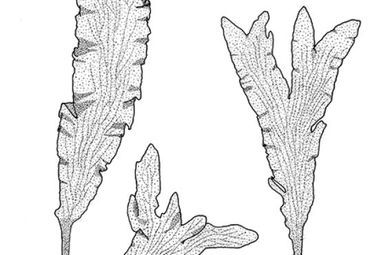

“I just thought it was an interesting story that this red alga looks so much like an animal, namely, a coral. It had been unnoticed as such, and then it turned out to have some distinctive features.”

Plant life plays a crucial role in fighting climate change by absorbing and transforming greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide. For instance, over its lifetime, a tree can absorb more than a ton of carbon from the air and store it in wood and roots.

This year’s theme was “Global Change and Its Consequences for Green Life,” and focused on the Direct and indirect impacts of environmental change on green life survival, reproduction, and distribution, how green life can buffer the impact of global change, evolutionary responses of green life to environmental change/stress, green life functional traits and their environmental correlates, and agroecology.

Birds across the Americas are getting smaller and longer-winged as the world warms, and the smallest-bodied species are changing the fastest.

The healthy herds hypothesis has even been used to suggest that manipulating predator numbers to protect prey might be a useful conservation strategy. Even so, hard evidence supporting the hypothesis is scarce, and in recent years many of its assumptions and predictions have been questioned.

Preserving the diversity of forests assures their productivity and potentially increases the accumulation of carbon and nitrogen in the soil, which helps to sustain soil fertility and mitigate global climate change.

Anthropologists have long thought that our ape ancestors evolved an upright torso in order to pick fruit in forests, but new research suggests a life in open woodlands and a diet that included leaves drove apes’ upright stature.

"A lot of people think plants are boring because they don’t move in the way animals do, but I think it makes them especially interesting. Plants can’t run away from a creature trying to eat them but, instead, they have more interesting defense mechanisms to protect themselves."

U-M ecologists Ivette Perfecto and John Vandermeer examine competition among the ant community at a Puerto Rican coffee farm and the maintenance of species diversity there.

There’s been a well-documented shift toward earlier springtime flowering in many plants as the world warms. The trend alarms biologists because it has the potential to disrupt carefully choreographed interactions between plants and the creatures that pollinate them. But much less attention has been paid to changes in other floral traits, such as flower size, that can also affect plant-pollinator interactions, at a time when many insect pollinators are in global decline.

The CT-scanned skull of a 319-million-year-old fossilized fish, pulled from a coal mine in England more than a century ago, has revealed the oldest example of a well-preserved vertebrate brain.

Imagine overhearing the Powerball lottery winning numbers, but you didn’t know when those numbers would be called—just that at some point in the next 10 years or so, they would be. Despite the financial cost of playing those numbers daily for that period, the payoff is big enough to make it worthwhile. Animals that live in highly variable environments play a similar lottery when it comes to their Darwinian fitness, or how well they are able to pass on their genes.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the problem of emerging pathogens and the unpredictable dangers they pose for human health, but what most people don’t realize, is that the same processes that promote the emergence of human diseases—international travel and commerce, wildlife poaching, deforestation and climate change—have caused similar outbreaks of devastating pathogens in wildlife populations.

Dolphins and other sea creatures are affected by human disturbances in their habitat, including climate change, overfishing, noise pollution from shipping, construction, oil exploration and navy sonar activity. These types of disturbances can interrupt important animal behavior like foraging for fish and socializing, but measuring disturbance is difficult because the animals live under water.

Efforts to promote the future health of both wild bees and managed honeybee colonies need to consider specific habitat needs, such as the density of wildflowers. At the same time, improving other habitat measures—such as the amount of natural habitat surrounding croplands—may increase bee diversity while having mixed effects on overall bee health.

Efforts to promote the future health of both wild bees and managed honeybee colonies need to consider specific habitat needs, such as the density of wildflowers. At the same time, improving other habitat measures—such as the amount of natural habitat surrounding croplands—may increase bee diversity while having mixed effects on overall bee health.

A new analysis of more than 20,000 trees on five continents shows that old-growth trees are more drought tolerant than younger trees in the forest canopy and may be better able to withstand future climate extremes.

When autumn arrives in the eastern United States and Canada, millions of monarch butterflies take flight, starting a 3,000-kilometer journey toward their overwintering locations atop a few mountain ranges in Michoacán, Mexico. Unlike avian migrants that similarly escape North America’s cold winters by venturing south, the monarch butterflies’ migration is a generational one.

Fish excretions. Yes, that’s fish pee. Could it improve food security in the Caribbean? Allgeier thinks so, and it might even help slow global warming.

The miles-wide asteroid that struck Earth 66 million years ago wiped out nearly all the dinosaurs and roughly three-quarters of the planet’s plant and animal species. It also triggered a monstrous tsunami with mile-high waves that scoured the ocean floor thousands of miles from the impact site on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, according to a new U-M led study.

Termites are critical in natural ecosystems—especially in the tropics—because they help recycle dead wood from trees. Without such decayers, the world would be piled high with dead plants and animals. But these energetic wood-consuming insects could soon be moving toward the North Pole and South Pole as global temperatures warm from climate change, new research indicates.

If you’re out walking through the woods on a sunny, wet afternoon, you might notice some pretty leaves or clusters of wildflowers. But when Chad Machinski (BS ’14) strolls through Nichols Arboretum, he not only knows the name of all the plants, trees, and insects he sees, but he also understands the intricate ways they are connected.

Katrina Munsterman, PhD student at U-M, recently became the recipient of a joint Sea Grant-NOAA Fisheries fellowship to pursue her work in ecosystem dynamics. Katrina applied via Michigan Sea Grant to receive this annual national award, the 2022 National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)-Sea Grant Joint Fellowship.

They are hunters, farmers, harvesters, gliders, herders, weavers and carpenters. They are ants, and they are a big part of our world, comprising more than 14,000 species and a large fraction of animal biomass in most terrestrial ecosystems.

For decades, biologists saw the marsupial way of reproduction as the more “primitive” state and assumed that placentals had evolved their more “advanced” method after these two groups diverged from one another. But new research is testing that view.

Around 13,200 years ago, a roving male mastodon died in a bloody mating-season battle with a rival in what today is northeast Indiana, nearly 100 miles from his home territory, according to the first study to document the annual migration of an individual animal from an extinct species.

Although many parasitic infections are not lethal, they can still impact health or animal behavior. For example, infected animals can eat less grass or other vegetation than they normally would. In an interesting twist, this means that a world with more sublethal parasitic infections is a greener world.

A new U-M study that used fossil oyster shells as paleothermometers found the shallow sea that covered much of western North America 95 million years ago was as warm as today’s tropics. The findings also hint at what may be in store for future generations unless emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases are reined in.

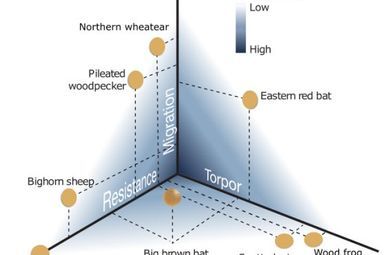

Animals have three main strategies to survive the freezing temperatures of winter: migrating, remaining in place and resisting the cold, and reducing body temperature and metabolic rate in a state called torpor. These cold-survival strategies are often studied in isolation by biologists and treated as mutually exclusive alternatives: An animal species is described as either migrating or hibernating (torpor includes both dormancy and hibernation), for example. But in reality, many animals combine multiple strategies to beat the cold.

U-M Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Nathan Sanders and his colleagues set out to test whether pollinators have a taste for salt in flower nectar.

A new U-M study has found that higher levels of biodiversity—the enormous variety of life on Earth and the species, traits and evolutionary history they represent—appear to reduce extinction risk in birds. Prior research has established that biodiversity is associated with predictable outcomes in the short term: diverse systems are less prone to invasion, have more stable productivity, and can be more disease resistant.

A new database called AVONET contains measurements of more than 90,000 individual birds, allowing researchers to test theories and aid conservation.