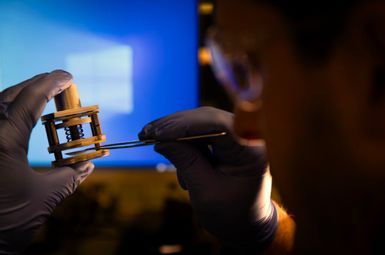

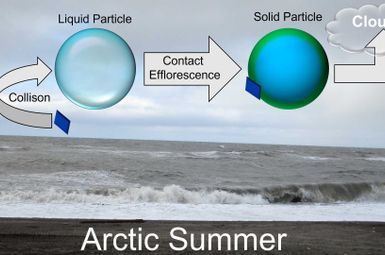

Water desalination plants could replace expensive chemicals with new carbon cloth electrodes that remove boron from seawater, an important step of turning seawater into safe drinking water.

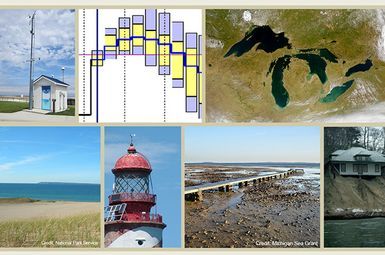

Extreme precipitation across the Great Lakes has increased by 35 percent over the past 65 years, causing lake levels to fluctuate at unprecedented rates. Meanwhile, studies have shown that by 2025, half of the world’s population will live in water-stressed areas. These changes in water quantity have devastated coastal communities and afflicted farmers who rely on water to produce crops. Researchers at the University of Michigan are working closely with community partners to explore pressing issues that impact water quantity, which affect everything from water quality, fish and wildlife to shipping, tourism and recreation.

Water desalination plants could replace expensive chemicals with new carbon cloth electrodes that remove boron from seawater, an important step of turning seawater into safe drinking water.

Anyone who’s spent their winter months around the Great Lakes has probably had the uncanny experience of living through three seasons in a single weekend. According to new research from U-M, these wild weather swings are poised to become even more common in the future.

As sea ice disappears and grows less reflective, the Arctic has lost around a quarter of its cooling power since 1980, and the world has lost up to 15%, according to new research led by U-M scientists.

“As people are worried about climate, we shouldn’t forget that a big part of the climate story is the ocean, which stores and transports a lot of heat and carbon.”

The ice-out, declared on March 16 this year, comes after the latest-recorded Douglas Lake “ice-in” occurred on Jan. 6—making this the shortest season of lake ice cover recorded at the U-M Biological Station, at 70 days. For 93 years, scientists at the Biological Station, the 10,000-acre research and teaching campus nestled along Douglas Lake near Pellston in the northern Lower Peninsula, have made the calls based on their observations of the lake.

U-M is marking late March and all of April with a series of events focused on sustainability and climate action, continuing a tradition that began with the first “Teach-In on the Environment” in 1970—which grew into what is now known as Earth Day.

When climate scientists look to the future to determine what the effects of climate change may be, they use computer models to simulate potential outcomes such as how precipitation will change in a warming world. But U-M scientists are looking at something a little more tangible: coral.

The global challenges posed by climate change are widespread, impacting various aspects of human life, with water resources at the forefront of these challenges. As climate change advances, it is projected to exacerbate water scarcity and access issues, given the intensification of water-related hazards (such as hurricanes and flooding) and rising temperatures that will lead to sea-level rise and saltwater intrusion.

This winter, researchers at the U-M Biological Station in northern Michigan are strengthening their snow science with new technology to track the snowpack at an hourly rate and get a deeper understanding of the complexities of global environmental change.

The need for a compact came when, twenty-five years ago, a Canadian company decided they could fill tanker ships with Great Lakes water to sell to countries with water shortages. Wanting to protect the lakes, the Great Lakes states, along with Ontario and Quebec, began the complex negotiations that would lead to the formal agreement detailing how they’d work together to manage as well as protect the Great Lakes.

U-M researchers will lead a new effort to strengthen the climate change resilience of vulnerable communities that span international boundaries and jurisdictions. The U.S. National Science Foundation has awarded $5 million to U-M to establish the Global Center for Understanding Climate Change Impacts on Transboundary Waters.

A new University of Michigan-led study finds that farmers in India have adapted to warming temperatures by intensifying the withdrawal of groundwater used for irrigation. If the trend continues, the rate of groundwater loss could triple by 2080, further threatening India’s food and water security.

The tools and policies that worked to significantly reduce threats to the Great Lakes over the past century are ill-equipped to handle today’s complex and interrelated challenges. A new set of stewardship principles is needed to work holistically and systematically on long-term social, economic, environmental, and racial-equity and resiliency concerns that have too often been sidelined in a rush for immediate results.

As climate change and population growth make water scarcity increasingly common, a much larger share of the global population will be forced to reckon with the costs of urban water scarcity. A new study sheds light on how households bear the monetary and nonmonetary costs when water supply is intermittent, rather than continuous—with policy implications that could help make urban water safer, more sustainable and more equitable.

“I wish to use this fellowship to answer these questions in the context of Mexico, documenting through “day in the life”-style illustrations of various people and communities interacting with water. I hope my findings can be transferable to other countries and regions facing similar challenges.”

A new analysis of more than 20,000 trees on five continents shows that old-growth trees are more drought tolerant than younger trees in the forest canopy and may be better able to withstand future climate extremes.

When an emergency causes a disruption in access to clean water, it seems reasonable to respond by providing the public with bottled water. In the short term, this can provide a safe supply of water while the problems get sorted out. But what if the emergency has lasted eight years, and counting, as it has in Flint, Michigan?

Many small and mid-sized communities like Goshen, IN simply don’t have the resources to tackle a global crisis like climate change on their own. So in 2018, Goshen was one of 12 cities that partnered with Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments (GLISA), an organization led by U-M that’s working to help small and mid-sized cities plan for a future that will be shaped by a changing climate.

"Water levels are getting lower and lower because of two big problems. First, the long agreed-upon annual allocation of water to about 40 million users in seven states (e.g., California) and Mexico exceeds the supply of water flowing in the river. Second, and ignored by many, the water flowing in the river is also dropping relentlessly, as a warmer, drier climate reduces the amount from snow and rain that reaches the river."

From the Great Lakes to its inland rivers and streams, hiking trails to golf courses, and lakeside cottages to campgrounds, the State of Michigan has long offered a near-endless number of natural resources to enjoy each summer—and a thriving tourism industry to prove it. But like with the rest of the country, and planet, the effects of climate change not only loom in the distance, but are here and causing real challenges to our ecosystem, and the outdoor recreation it provides, right now.

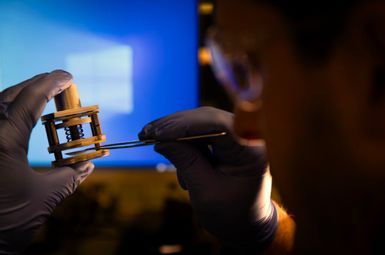

U-M researchers and their partners are forecasting that western Lake Erie will experience a smaller than average harmful algal bloom this summer, which would make it less severe than 2021 and more akin to what was seen in the lake in 2020.

U-M has been awarded a five-year, $53 million renewal agreement from the federal government to continue and expand the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research, with the goal of helping to conserve and manage the region’s natural resources.

The Great Lakes Impact Investment Platform announced the environmental performance of its participating projects across eight U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Collectively, the projects are reducing 3 million tons of carbon, protecting more than 30,000 acres of forest and farmland, saving 110 million kilowatts of energy, and saving 5.4 million gallons of water.

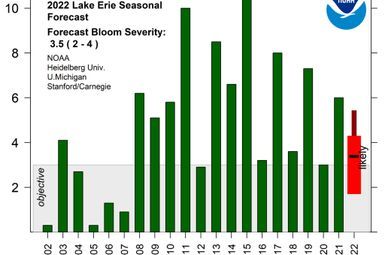

The Arctic is rapidly losing sea ice, and less ice means more open water, and more open water means more gas and aerosol emissions from the ocean into the air, warming the atmosphere and making it cloudier. So when U-M researchers collected aerosols from the Arctic atmosphere during summer 2015, Rachel Kirpes, then a doctoral student, discovered a curious thing: aerosolized ammonium sulfate particles didn’t look like typical liquid aerosols.

Maps of the American West have featured ever darker shades of red over the past two decades. The colors illustrate the unprecedented drought blighting the region. In some areas, conditions have blown past severe and extreme drought into exceptional drought. But rather than add more superlatives to our descriptions, one group of scientists believes it’s time to reconsider the very definition of drought.

The Great Lakes support more than 3,500 species of plants and animals, including more than 170 species of fish, and a population of 34 million people in the United States and Canada who rely on these waters for recreation, employment, drinking water supply, and more.

Teams will drill through ice to collect water samples, measure light levels at various depths and net tiny zooplankton as part of a broader effort to better understand the changing face of winter on the Great Lakes, where climate warming is increasing winter air temperatures, decreasing ice-cover extent and changing precipitation patterns.

In recent years, lakeside communities have struggled to cope with the effect of rising water levels and erosion on the beaches that have made them such attractive places for vacationers and residents alike. As a professor of urban and regional planning, Richard Norton’s work explores how humans can safely adapt to these environmental changes, while also protecting the unique ecosystems that make the Great Lakes region special.

Without a sustainable water supply, life in the desert is all but impossible. Flows of the Colorado are steadily shrinking because it’s snowing and raining less in the headwaters. Even bigger reductions in river flow have occurred due to the impact of relentless global warming.

Carter, an assistant professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability, received a grant from the NASA Biodiversity and Ecological Forecasting program to research how changes in vegetation canopy and water stress in the western U.S. affect large mammal species.

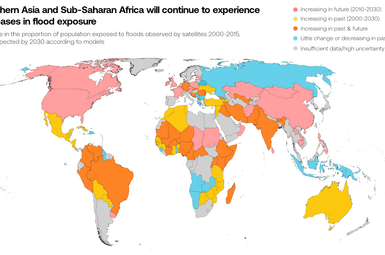

New research used direct satellite observations of floods to reveal that the proportion of the world’s population exposed to floods has grown by 24% since the turn of the century—10 times higher than scientists previously thought—due to both increased flooding and population migration.

The world’s largest ice sheets may be in less danger of sudden collapse than previously predicted, according to new findings led by U-M. Researchers modeled the collapse of various heights of ice cliffs—near-vertical formations that occur where glaciers and ice shelves meet the ocean. They found that instability doesn’t always lead to rapid disintegration.

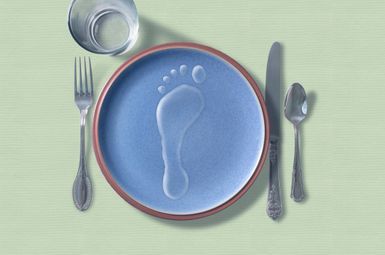

A lot of attention has been paid in recent years to the carbon footprint of the foods we eat, with much of the focus on the outsize contribution of meat production and especially beef. But much less is known about the implications of individual U.S. dietary choices on other environmental concerns, such as water scarcity.

How will fluctuating water levels across the Great Lakes impact the growth of cities, people moving to the region, changes in water supply and the overall economy? Professor Drew Gronewold is working with researchers across U-M to answer those critical questions.

The country that produces 10% of the world’s crops is now the world’s largest consumer of groundwater, and aquifers are rapidly becoming depleted across much of India.

.jpg)

Discussions of drought often center on the lack of precipitation. But among climate scientists, the focus is shifting to include the growing role that warming temperatures are playing as potent drivers of greater aridity and drought intensification.

Drew Gronewold discusses the impact that climate change is having on lake levels in the Great Lakes, and how his research can contribute to predictive models that can inform future policy decisions.

Drew Gronewold and Richard Rood explain how a series of historically damaging floods “serve as warnings that we must better prepare and plan for the future ahead.”

Drew Gronewold and Richard Rood say the rapid transitions between extreme high and low water levels in the Great Lakes represent the “new normal.”

Highly localized and accurate Great Lakes ice cover forecasts have been demonstrated by researchers at U-M, and their predictive modeling tool can be adapted for any geographic region. Such localized forecasts would be useful more broadly as climate change brings a roller coaster of weather variability to many parts of the world, including those who live along, play in and make their living from the world’s largest surface source of freshwater.

Great Lakes water levels are continuously monitored by U.S. and Canadian federal agencies in the region through a binational partnership. NOAA-GLERL relies on this water level data to conduct research on components of the regional water budget and to improve predictive models.

After more than a decade of decline, water levels in Lakes Michigan and Huron reached historic lows in 2013, impacting the economy and ecology of the region. Then, during 2013 and 2014, the lakes nearly set another record as they experienced one of the largest two-year gains in water levels in recorded history, underscoring the dynamic nature of the Great Lakes system.

One U-M engineering alumna describes her work at Toolik Field Station, a world-renowned Arctic research outpost deep in Alaska’s interior.